This week finds me in the Lake District; specifically, I'll be spending my days in the

Jerwood Centre at Dove Cottage. Blogging this week will temporarily offer different fare, then: my week among the 65,000 manuscripts and rare books on offer in this idyllic part of England. (A shorter way of saying this would be "Romantic researcher heaven".) I will try and refrain from harping on about the amazing breakfasts, courtesy of my base for the week at the rather lovely

Forest Side Hotel (but they deserve several posts on their own).

|

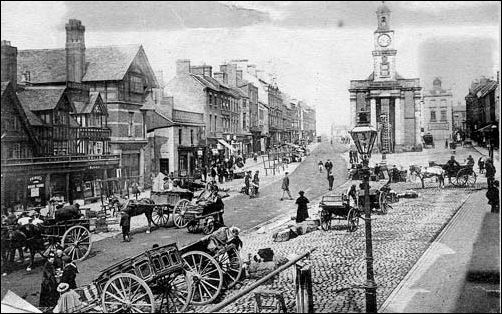

Photo: Jo Taylor. Young enters North Staffs, leaving Cheshire

with a dig about their rubbish horses. |

Aside from attempting (badly) to decipher the letters of Coleridges writing in various degrees of sobriety, I'm doing a few tasks for the Jerwood Centre team. My first task this morning involved delving in to Arthur Young's four-volume account,

A Six Months Tour Through the North of England (1771). The account begins near Hull, and follows Young on his journey south, along the way taking in Newcastle-on-Tyne, Yorkshire, the Lake District, Liverpool, Lancashire and Cheshire, among other places. Young toured the country, visiting local landmarks and, essentially, comparing the different methods of cabbage-growing. Young discusses the soil quality of the areas he visits, examines the local industry (including the wages of the workforce), and includes diagrams of the farm machinery in use.

Fascinating though I undoubtedly find the growing habits of different varieties of 'ternips', it wasn't the agricultural information that caught my eye. No, what really got my attention was scan-reading a page, only to see the phrase "I had the pleasure of viewing... Burslem". Naturally, I had then to read on.

Young enters into a detailed description of the various manufactories around "Newcastle-under-line". He credits the famous Mr. Wedgwood with establishing a thriving local economy; all other potters, he says, are "little better than mere imitators". Mr. Wedgwood has, it seems,

lately entered into partnership with a man of sense and spirit, who will have taste enough to continue in the investing plan, and not suffer, in case of accidents, the manufactories to decline.

How this relates to the Potteries now, I will leave for others to discuss; needless to say, perhaps, that a similar man "of sense and spirit" would find plenty to do nearly two and a half centuries later! Regardless, Young's congratulation of North Staffordshire generally, and the

Wedgwood potteries particularly, serve as a quaint reminder of the hope invested in the Stoke-on-Trent area at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, when the Burslem potteries were on the cutting edge of industrialisation and the technology that went with it.

|

| Photo: Jo Taylor. Newcastle: home of hats. |

Newcastle and the land south of it towards

Stone, on the other hand, is praised for its "beauty" - but it's not the picturesque description Young indulges in when discussing the Yorkshire fells or the "cataracts" of the Lakes (invocations of the sublime and beautiful that would make Coleridge and Wordsworth take to their notebooks). No, Newcastle and the surrounding land is praised for a different kind of beauty; a more specialized version, if you will: "From Newcastle southwards the country improves greatly in beauty: The soil towards Stone is generally a sandy loam." Young, to give him due credit, has the mind of the truly optimistic pragmatist: Burslem is fortunate to lie in the midst of such an apparently unending profusion of coal, and Newcastle's ability to grow a wide variety of crops (although sadly some farmers adopt 'a vile as well as strange' course in the rotation of these). Newcastle did not only rely on agriculture, however: it also possessed "a considerable manufactory of shoes and hats". The shoe workers earned significantly less than those in the hat business: a worker in a shoe factory earned between 10d and 2s a day, whilst those in the hat line earned 7-10s a week. (Young seems to engage in some subtle social criticism when discussing wages; his alternations between daily and weekly calculations often seems designed to shock the reader.)

|

Photo: Jo Taylor. Young considers local agricultural practices.

Cows & potatoes good.

Beans bad. |

Nevertheless, Young presents an image of North Staffordshire that fits in well with his idyllicised descriptions of the more northerly parts of England. Certainly, it is an optimistic representation to the point of outright falsehood; although we may find traces of social criticism, Young deliberately overlooks the poor working and living conditions of the "Poor man". Regardless, it's a good reminder of the things Stoke still does have to offer. We're told that

Hollywood directors are being invited to Stoke; maybe they should follow Young's footsteps.

|

| Photo: Jo Taylor. Young heads on towards Rugeley |

.jpg)